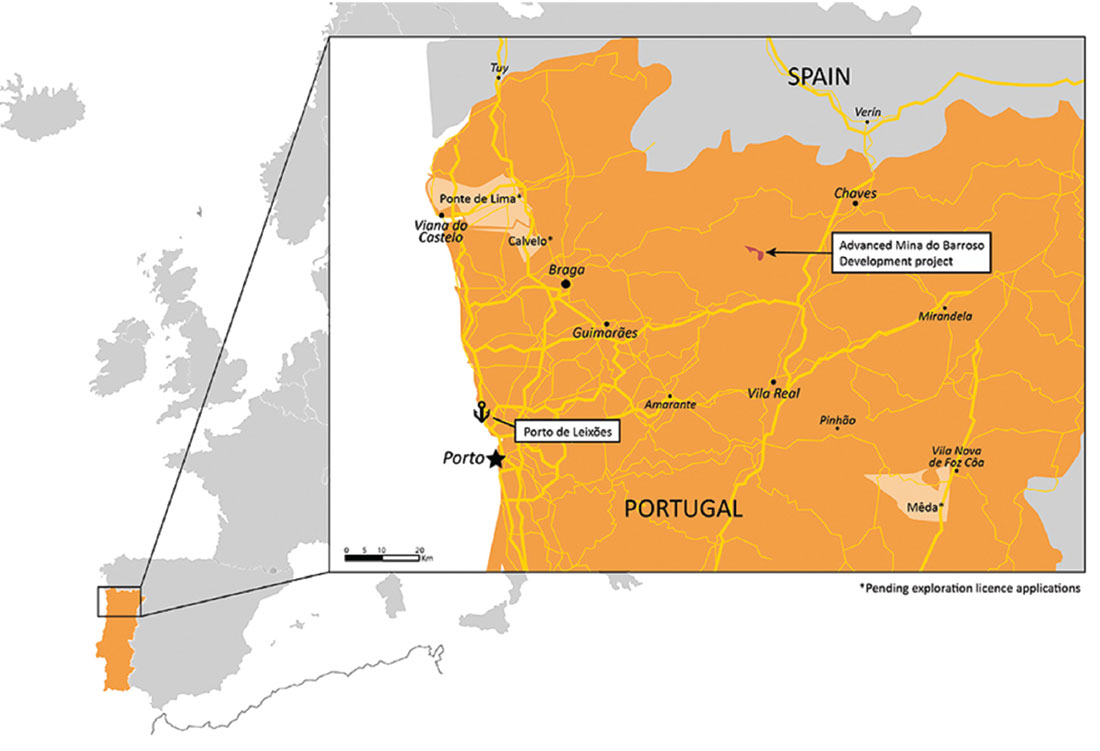

With global demand for lithium ramping up, major economic blocks are frantically trying to secure sufficient supply for the precious metal. Expected surges in sales of EVs and battery storage devices are dependent on lithium. Portugal is the largest lithium producer in Europe. If all’s going to plan, the Portuguese will add a mine annex production unit to the roster: Mina do Barroso.

By Lucien Joppen

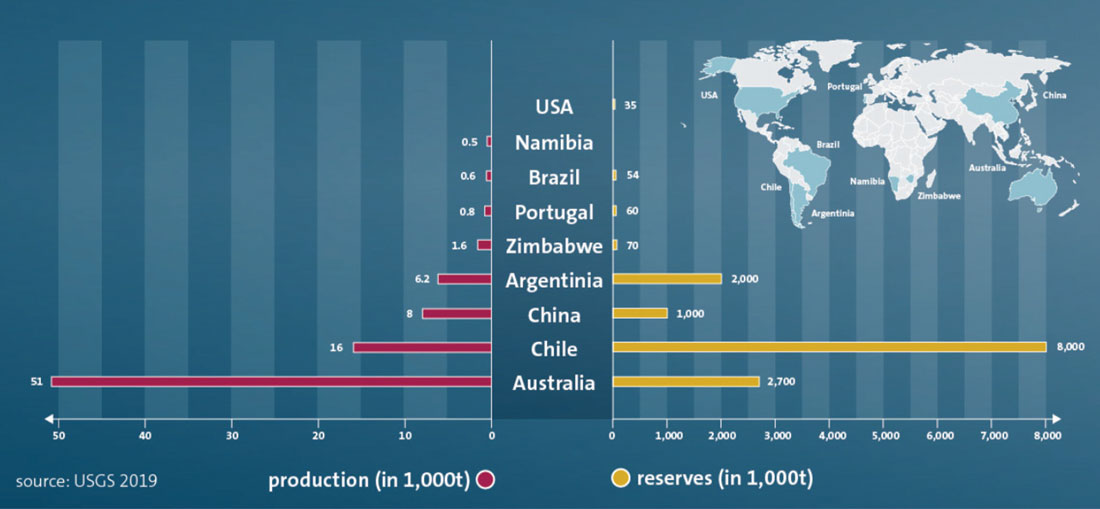

Portugal is already at the top of Europe’s lithium mining sector, providing roughly 11 per cent of the global market. However, this output is not used for energy purposes but used in its entirety for the produc-tion of ceramics and glassware.

The country’s potential is significant and not to be overlooked. Portugal is the world’s sixth-largest lithium-producing nation, and the top producer among European countries with an output of 1,200 tonnes in 2019.

According to USGS data, the country holds around 250,000 tonnes of lithium resources and 60,000 tonnes measured in mine reserves. The aforementioned Mina do Barroso Lithium Project in northern Portugal – owned and operated by UK-based Savannah Resources – is Europe’s most significant deposit of lithium-containing spodumene ore.

According to Savannah, metallurgical tests have shown that the quality of the lithium makes it ideal for the EV battery industry. This would add a significant supply to the EU car industry, which up until today is dependent on South American, Australian and Chinese supply.

Security of supply

The latter would not be an ideal situation for an economic block that harbours many of the leading car manufacturers in the world. With the likes of Volkswagen investing heavily in EV-development and production, one wouldn’t want to stunt this advance with a lack of raw materials.

As a result, major economies, such as the EU and the US, have increasingly implemented policies to secure critical minerals sourcing and diversify away from China. Understandably, an important policy is to stimulate and develop a domestic lithium supply chain (mining and processing). Currently, there are several projects in various stages of development on the continent. Many of these projects are centered in the German, Austrian and Czech region. Just to give an example, the Zinnwald lithium project is located in the heart of Europe’s chemical and car industries, about 35 kilometres from Dresden.

Other key lithium projects to be developed in the EU include CEZ Group and European Metals’ Cinovec project in the Czech Republic or the Austrian Wolfsberg-project. Many of these projects are expected to come online around 2023-2025.

Conversion plant

Mina do Barroso could join the roster. The project holds a resource estimate of 20 million tons of lithium with over 200,000 tons that contain Li2O. Also, the project would include a processing facility to purify and upgrade the raw material. The objective is to keep the value chain intact as the raw material should be destined for the EU market. For this purpose, the energy company Galp have formed the joint-venture Aurora with the Swedish battery storage company North-volt. Both companies aim to build Europe’s largest and most sustainable integrated lithium conversion plant. The facility in Portugal is set to have an initial annual output capacity of up to 35,000 tons of battery grade lithium hydroxide, a material needed in the production of lithiumion batteries. This volume is enough to power 700,000 electric vehicles. The plant could represent an investment of about ¤700m and create up to 1,500 direct and indirect jobs. Aurora expect to start commercial operations in 2026, pending a final investment decision.

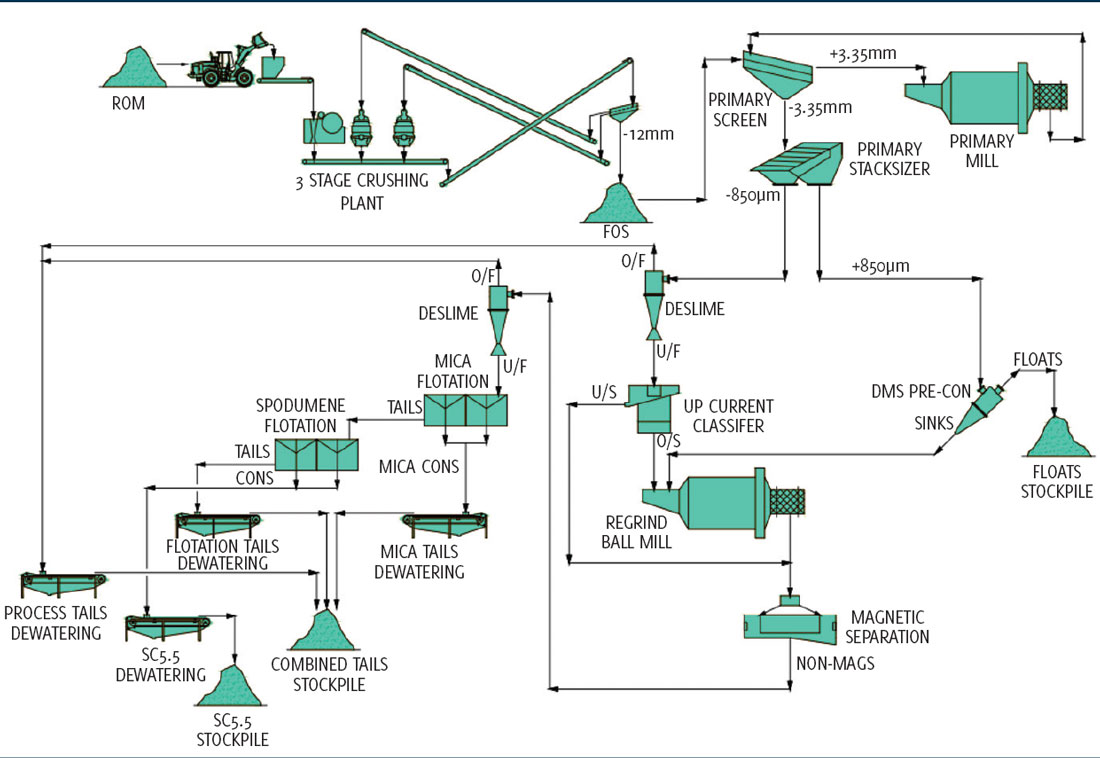

As part of the ongoing DFS work, Savannah announced in February 2022 that it had final-ised the design on the process flowsheet. Savannah believes the Project’s location and near-term production potential will make its product highly sought after and it can act as a strategic up-stream foundation for the build out of a lithium value chain in Europe. Project highlights:

• The flowsheet will utilise industry standard equipment and processes including Dense Media Separation, pre-concentration, followed by magnetic separation and flotation

• The environmentally friendly reagent regime, which complies with all known European and Portuguese requirements, allows both mica and spodumene flotation to operate at near neutral pH

• Results from the samples tested to date have achieved Li2O recoveries in the range of 70-79.5% at laboratory scale with low levels of impurities. Average recovery achieved for all composites is 75.3%

• Process performance has been optimised at a 42% coarser grind size (150 micron (‘μm’)) than previously tested which should result in significant capital and operat-ing cost savings

• An opportunity exists to double the grind size (212 micron) versus the previously reported level (106 micron) for approximately 40% of the tested resource with the potential for average recoveries of c.80%

• Co-product testing has confirmed the potential to generate saleable ceramic products from the processes waste streams

• Based on the positive results achieved to date, locked cycle test work and planning for the pilot plant test work program are underway Source: Savannah

Environmental impact

As with all economic activities, lithium mining is associated with environmental impact. Lithium from brine resources (for example Chile) has been researched extensively regarding its impact on the environment and the local population. With spodumene coming more into the picture, this impact is still terra incognita, says Dr John L Burba, CEO of International Battery Metals, a company that develops technology to facilitate so-called green lithium. According to Burba, spodumene-based lithium is also more under the radar as China is the main processor of this resource. This position, however, does not warrant research on the environmental impact and the development of measures/technologies to reduce this impact. With present commitments of car industry makers to use sustainably sourced lithium, this is not a mere option but more a license to produce.

It is no surprise that each step in spodu-mene processing to battery-grade products needs a lot of energy. Post-mining and crushing, all of the remaining steps require significant additional chemical input.

Decarbonisation strategy

Savannah has announced that it intends to design and operate the Barroso Lithium Project in a way which minimises its impact on the natural environment. “While maximising the benefits to local communities and society, ensures its lithium product carries a minimal carbon footprint into the lithium battery supply chain.”

To complement the highly comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment submitted on the proposed development to Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente, (APA), the Portuguese Environmental Agency, Savannah announced the initiation of a decarbonisation strategy for the Project in March 2022. “Working with leading consultants and service providers in the field, Savannah is committed to moving towards reducing the Scope 1 and 2 emissions at the Barroso Lithium Project to net-zero once in production and, ultimately, to a position of net zero life-of-project, and targeting the reduction of its Scope 3 emis-sions in collaboration with its future customers.”

Competition

Apart from addressing the environmental impact, Mina do Barroso also has to compete on the global market. This might be a challenge as its lithium is roughly 2.5 times more expensive than lithium that is won from brine fields. A plus is that the afore-mentioned metallurgical studies have shown a 6 percent Li2O low impurity concentrate, which according to Savannah, is ideal for the EV market.

The open-pit mine will also yield a feldspar and quartz co-product destined for the ceramics industry customers in the domestic market and its Iberian neighbour Spain.

In terms of project development, Mina do Barroso is still in the definitive feasibility stage (DFS). Once the DFS has been com-pleted, the Group expects to be in a position to make a final investment decision.