Reverse osmosis system for water drinking plant. Photo: Dreamstime.

The climate crisis is exacerbating water scarcity. Fortunately, however, technologies are emerging that will make water management more efficient and sustainable. Advances in recycling, membrane and filtration technologies, use of renewable power and new materials are transforming the water industry.

By James Chater

What’s at stake

The current year has highlighted both the climate crisis and the perils of ignoring it. The summer, one of the hottest and driest on record, was marked by devastating wildfires, while floods swept through Europe, Asia and the Americas. Water – or its absence – sits at the crossroads of these challenges. Scarcity threatens to make vast regions uninhabitable, while wildfires require abundant supplies to fight the flames. Meanwhile, sudden, intense rainfall underscores the need for smarter flood prevention and mitigation. Depending on the circumstances, water is both a problem and a solution.

Desalination

Desalination, once considered a last-ditch option, is now a vital tool against scarcity. Critics rightly point to its energy intensity and brine by-products, but technological advances are steadily making it more sustainable.

Hong Kong’s Tseung Kwan O desalination plant, commissioned in 2024, is a case in point. Built on reclaimed landfill, the site avoids disrupting new habitats while placing production close to population centres and existing pipeline networks ensures efficient distribution. The plant uses ActiDAFF, a hybrid flotation–filtration system that adjusts energy use based on water quality: energy use is reduced when water impurities are low. Advanced reverse osmosis (RO) with energy recovery devices can reclaim up to 96% of the brine’s pressure energy, cutting pumping energy requirements by half. High-efficiency pumps and a 10 MW solar farm, along with over 1,800 rooftop solar panels, will further slash the plant’s carbon footprint. Rainwater harvesting and greywater reuse are expected to halve freshwater consumption.

Across the Middle East and North Africa, desalination plants are pushing capacity boundaries. The Shoaiba complex in Saudi Arabia holds the record for the world’s largest water desalination capacity, at nearly 3 million cubic metres per day. Other mega-projects include the Ras Al Khair hybrid plant (Saudi Arabia), and Jebel Ali, Fujairah and Taweelah (all in UAE). These plants combine advanced thermal and RO technologies to maximise output while improving energy efficiency.

In Morocco, drought conditions and declining rainfall have accelerated investment in desalination infrastructure. A plant near Agadir, inaugurated in 2022, supplies both drinking water and irrigation water to critical agricultural zones. By 2031, Morocco plans to host four of the world’s ten largest desalination facilities.

Renewables are increasingly integrated: Oman’s Sharqiyah desalination plant recently inaugurated a 17 MW solar power installation, capable of supplying over a third of the plant’s electricity needs and reducing CO2 emissions by 27,200 tonnes per year. In terms of overall efficiency, Veolia’s Mirfa 2 plant in Abu Dhabi promises to break new ground: it will deliver 550,000 cubic meters per day of potable water while reducing energy use by up to 80% compared to older thermal systems.

Smaller-scale plants are also making a significant impact. In Tunisia, Lantania is constructing a 7,500 cubic metres per day RO desalination facility for the company Agro Care, aimed at irrigating greenhouse crops. Even smaller are the modular MBR systems that enable small communities and industries to gain access to advanced treatment without large infrastructure investments.

Recycling

If desalination expands supply, wastewater reuse exemplifies sustainability by transforming waste into a resource. Increasingly, water treatment is being tailored to end use, whether irrigation, industry or drinking water. Potable reuse is no longer experimental: it is established in Singapore, Namibia, and parts of the USA and Europe, with new projects under way in Perth, El Paso, San Diego and Los Angeles.

Did you know

Solar desalination is older than many realise: it dates back to 1942, when Hungarian American scientist Mária Telkes designed a portable solar distillation device for the US military, providing lifesaving fresh water for stranded pilots and sailors. Her pioneering work earned her the nickname “Sun Queen,” reminding us that innovation in water technology often builds on a long lineage of ideas.

New technology

Several important trends are reducing costs and making water management more sustainable. For example, membrane bioreactors (MBRs) combine biological treatment with advanced membrane filtration, such as microfiltration or ultrafiltration. The result is higher-quality effluent, whether in municipal or industrial wastewater treatment, or recycling. MBRs reduce the footprint of treatment facilities, are adaptable for retrofitting, and have been deployed in projects world-wide, from Owatonna, Minnesota, to St Helena, California, and Thiruvananthapuram, India.

Forward osmosis (FO) reduces energy demand and fouling by relying on osmotic gradients rather than high-pressure pumps.

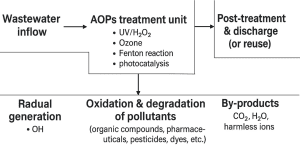

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are emerging as a tool for achieving high quality in drinking water. They remove organic (and sometimes inorganic) materials in water and wastewater by oxidation through reactions with hydroxyl radicals. AOPs are highly effective, as they can remove over 99% of contaminants, mineralise organic carbon into harmless byproducts, and even achieve simultaneous disinfection. However, AOPs are energy-intensive and costly, so they are generally used only in the final stages.

Water treatment and renewable energy are increasingly entwined. Saudi Arabia’s planned NEOM/OXAGON desalination plant, powered entirely by green hydrogen and renewables, is emblematic of this shift. Morocco is coupling desalination with wind power; Dubai’s Hassyan SWRO and Ukraine’s Mykolaiv solar desalination project are harnessing solar. Not only will the future of water be powered by clean energy, but the converse is also true: wastewater can be converted into energy, as happens at the biogas unit at the Seine Aval wastewater facility near Paris. These projects illustrate a convergence of water treatment, energy efficiency and climate-conscious design, highlighting that future water infrastructure will not only secure supplies but do so sustainably.

Valves used in water treatment

Valves are essential for any water application, from extraction to treatment to transportation. The most commonly used valves for water treatment are:

- Gate valves: Used for isolation, ie fully open or closed, not for throttle. Gate valves provide low flow resistance when open and a tight shutoff

- Butterfly valves: Used for on/off or throttling control, these are the go-to valves for large diameters.

- Ball valves: Used for smaller diameters or auxiliary line. Vall valves provide a quick shutoff with minimal pressure drop.

- Check valves: Also known as non-return valves, these are essential for preventing back flow

- Globe valves: Commonly used wherever flow regulation of throttling is needed.

- Air release/vacuum valves: These are crucial for long pipelines and high points

- Pressure reducing & control valves: These automatic valves maintain a stable downstream pressure in water systems.

Size matters

Water treatment and transport often utilses large-sized valves. For large transmission pipelines (those carrying treated or raw water from reservoirs or treatment plants to cities), these include:

Water treatment and transport often utilses large-sized valves. For large transmission pipelines (those carrying treated or raw water from reservoirs or treatment plants to cities), these include:

- Butterfly valves are typically used for diameters up to DN 3000 mm (≈120 in /10 ft).

- Gate valves are common up to about DN 1200–1600 mm (≈48–64 in); beyond that, they become uneconomical and too heavy to operate reliably.

- Check valves (swing or dual-plate) are also made up to around DN 2000 mm (≈80 in), but are usually installed smaller than the main isolating valves.

However, if we consider mega-scale water transport systems such as long-distance aqueducts, hydro schemes, or inter-basin transfers, manufacturers such as AVK, Bermad, Singer, and KSB have produced butterfly valves up to DN 4000 mm (≈160 in / 13 ft). These are rare and custom-made, typically used at dam outlets, pumping stations, or hydropower penstocks.

Materials

Duplex stainless steels, which combine strength with resistance to chloride-induced corrosion, have become standard in modern desalination units. Over the years there has been a trend to replace austenitics and superaustenitics with duplex and super duplex grades. By comparison, duplex grades offer lower embodied energy, reduced nickel content and longer service life. They are now specified in major desalination plants, from Tel Aviv to the Gulf, where durability and cost-efficiency are paramount.

If duplex steels are the staple of today’s installations, nanomaterials promise to redefine membranes in the future. Graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, and nano-adsorbents are moving from lab to pilot scale. In Australia, NematiQ and Monash University are advancing graphene membranes under a government-backed feasibility program. In the US, SBIR-funded prototypes using CNT-enhanced distillation membranes are preparing for pilot trials. Japan’s Water Plaza Kitakyu¯ shu¯ has already tested nanocomposite membranes in real seawater, providing valuable operational data.

Rather than replacing mainstream seawater RO in the near term, nanomaterials are likely to enter the field as complementary solutions: pretreatment filters or niche separation membranes.

Nevertheless, nano-engineered materials are steadily advancing from lab benches to pilot tanks, setting the stage for a new generation of membranes that could cut energy use and broaden the scope of water reuse.

Conclusion

New technology combined with next-generation materials are transforming the water industry, making it more sustainable and integrating it with renewable energies and environmental management. Costs have been tumbling, and we must hope that this trend will continue, so that environmental upgrades can be carried out even in the world’s poorest regions, where the need is often the greatest.

Dive Deeper into Valve World

Enjoyed this featured article from our November 2025 magazine? There’s much more to discover! Subscribe to Valve World Magazine and gain access to:

- Advanced industry insights

- Expert analysis and case studies

- Exclusive interviews with valve innovators

Available in print and digital formats.

Breaking news: Digital subscriptions now FREE!

Join our thriving community of valve professionals. Have a story to share? Your expertise could be featured next – online and in print.

“Every week we share a new Featured Story with our Valve World community. Join us and let’s share your Featured Story on Valve World online and in print.”