^ Maersk: “The technical ways of reducing carbon emissions are drying out for container shipping”.

Article By Ellie Pritchard

In 2019, international shipping depended for more than 90 per cent on heavy sulphur fuel oil (HSFO). But recent environmental regulations have seen fluctuations in HSFO demand. The question is: will HSFO become obsolete as other, lower sulphur grades are becoming mainstream?

As of January 2020, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) enforced a cap on sulphur percentage used in marine fuel to 0.2 per cent in efforts to improve air quality, preserve the environment and protect human health. With more than 53,000 merchant ships on the ocean, accounting for around 5 billion barrels of fuel per year (over 6% of global oil use), sulphur reduction in the marine sector will have a significant positive impact.

Recent regulations have forced the marine industry and all interested parties to think fast about what the future of shipping will look like, both in the short- and longer term.

The IMO 2020 regulation means shipping companies must either switch to a lower sulphur option such as low (LSFO) or very low sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO) or install scrubbers (exhaust gas cleaning systems) enabling them to continue with the cheaper HSFO. These changes in the marine industry raise questions as to the future of marine fuel oil and certainly complicate market predictions.

The key questions for most shipping companies, marine industry investors, and refineries alike: What does the short- and mid-term future of marine fuel look like? Does HSFO still have a place in the market? Valve World magazine made contact with some of these industry voices to ask them what the future of marine fuel means for them and their position in the marine sector.

Complete flip

ING Group is an important investor in marine shipping. The bank has signed a €300 million agreement with the European Investment Bank (EIB) to support green investment for the shipping sector. Warren Patterson, Head of Commodities Strategy for ING, sheds light on the short-term future of shipping fuel.

“Bunker fuel demand is in the region of 4.5m barrels per day, and the bulk of this demand is for VLSFO and marine gasoil (MGO) as it meets the IMO 2020 sulphur regulations”, Patterson says. “If we look at the largest bunkering hub in the world, Singapore, almost 80 per cent of bunker sales in 2020 were for VLSFO, MGO or ULSFO, whilst HSFO made up 20 per cent of sales. This is a complete flip from the previous year, where almost 80 per cent of sales were for HSFO, and around 20 per cent for VLSFO, MGO and ULSFO.”

Premium has shrunk

HSFO, being the bottom of the barrel substance produced in enormous quantities by most refineries, has always been the cheaper option for ships to run on. For this reason scrubbers, although an expensive investment, are a feasible alternative to shifting towards more expensive lower sulphur fuel options.

But, as Mr Patterson explains, this has not necessarily been the case. “In the lead up to the new sulphur regulations, VLSFO was trading at as much as US$290/t premium to HSFO, and so it made sense for shipowners to install scrubbers, with a very short payback period. However, the premium for VLSFO has shrunk significantly over 2020, below US$50/t at one stage, leaving it less certain that shipowners would go the scrubber route, and so instead use VLSFO. In fact, over the course of 2020, there were even reports of owners cancelling scrubber installations.” This has come from an oversupply in VLSFO, linked to Covid-related reduced demand (see Graph 1).

Indeed, as reported by S&P Global Platts the spread between 0.5 and 3.5 per cent sulphur fuel oil was at its widest on 3 January 2020, at $321.50/mt. Following the widespread impact of COVID-19 on oil markets, the spread dropped 88 per cent to $38/mt on 4 June 2020.

Not the end for scrubbers

However, Mr Patterson does expect to see a widening in the spread between VLSFO and HSFO which would renew interest in scrubber installations. “We would expect to see less jet fuel or vacuum gasoil diverted to VLSFO as we see a recovery in road fuel and aviation fuel demand following COVID-19. This should tighten up the availability of VLSFO. Also, as OPEC+ eases their production cuts, we should see more heavy crude oil returning to the market, and as a result increasing HSFO-availability from refiners.” And indeed, as of early January 2021, the differential between HSFO and VLSFO has been improving. In Singapore it was in the order of $80, Rotterdam, $73 and Fujairah, $106. ING’s outlook mirrors that of Platts Analytics which anticipates that by December 2021 vessels with scrubbers are likely to account for over 1 million bpd of HSFO-demand.

However, in the long-term, Mr Patterson views biofuels and LNG as the path ahead. “LNG has an opportunity to play a key role in lowering emissions for the shipping industry. LNG supply should continue to grow in the years ahead with a number of liquefaction plants in the pipeline. Therefore, there shouldn’t be an issue in meeting growing demand. The one issue though that may prove to be an obstacle in the near term, is limited LNG bunkering infrastructure, but obviously with time this should be overcome.”

The market tries to rebalance

But, with infrastructure for bunkering LNG still needing work and biofuels remaining a costly option, both of these alternatives are solutions for the long term. Returning to the short-term, in terms of market outlook, ING anticipates a rise in marine fuel prices from now into 2022 as the global oil market tries to rebalance after OPEC+ production cuts, which set to continue into next year.

Warren Patterson: “In addition, we expect oil demand to continue recovering, and as we move through 2022, we believe that oil demand should reach 2019 levels once again. We expect ICE Brent to average US$65/bbl over 2022, but clearly given the growing investor interest that we are seeing in oil and the broader commodities complex, there is the potential for further upside to this.”

Silver bullets

The world’s largest shipping company, Maersk, presented its outlook in the IMO’s symposium on alternative low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels in February 2021. Simon Bergulf, Director of Regulatory Affairs for A.P. Møller – Maersk, explained that as a company with over 750 vessels using more than 11.6 million tonnes of fuel per year, Maersk had realised the need to accelerate its own strategy.

“The technical ways of reducing carbon emissions are drying out for container shipping, and it’s really going to be about the new fuels,” said Mr Bergulf. “We believe that the time of having one general fuel for shipping is over, we are likely to have a situation where we will have a number of different fuels. We don’t know which ones will be the silver bullets, but we do know that they are likely to be far more expensive than the fuels we are sailing on now. Most of the research and development will have to come from fuel suppliers”.

With shipping giants such as Maersk calling on refineries for further exploration of fuel options, it is clear that HSFO may not have a place in the long-term future of the maritime sector.

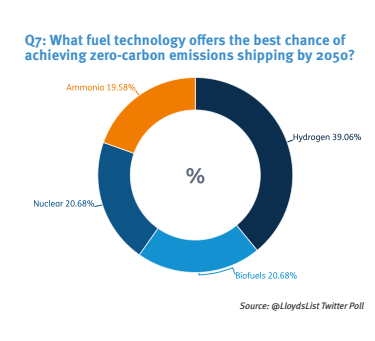

Q7: What fuel technology offers the best chance of achieving zero-carbon emissions shipping by 2050?”.

Neste: focus on transportation decarbonisation

Finnish energy company Neste does not have HSFO in its marine fuel oil offering, although towards the end of 2019 the company expanded its product portfolio to include IMO 2020 compliant products. However, it is not necessarily that Neste is investing in sulphur fuels for the future. Another initiative proposed by the IMO is the GHG (greenhouse gas) strategy intending to reduce CO2 emissions across international shipping by 40 per cent by 2030 and pursuing further efforts towards 70 per cent by 2050.

Sveta Ukkonen, Head of Marine Fuels and Services, says “I cannot disclose exactly what our future product offering will be like, but I can say that providing renewable and circular solutions is at the essence of Neste”.

For refiners and energy companies, the changes in marine fuel oil regulation mean reassessment of product offering and the capabilities of existing facilities, not only for the long-term but also for the immediate future. In Neste’s report ‘Taking Action on Climate Change’ printed in 2017, the company’s senior strategy advisor Lauri Kärnä admitted “Fossil fuels are not about to disappear, and their demand will in fact continue to increase globally towards 2030 and beyond. However, as demand turns to decline in our home markets around the Baltic Sea, Neste and the sector will have to adapt. EU refiners need to take other actions, and co-processing could be one of these.”

Q10: What is the best investment opportunity for shipping in 2021?”.

In 2020, restricted travel resulted in a significantly reduced fuel demand. In terms of local demand, Neste experienced a significant drop in its output to Swedish and Finnish cruise liners which of course saw a heavily reduced business for most of 2020. As a result, energy transition plans were sharpened, and many refineries found themselves scaling back on oil refining and instead placing more focus on cutting greenhouse gas emissions at their remaining sites.

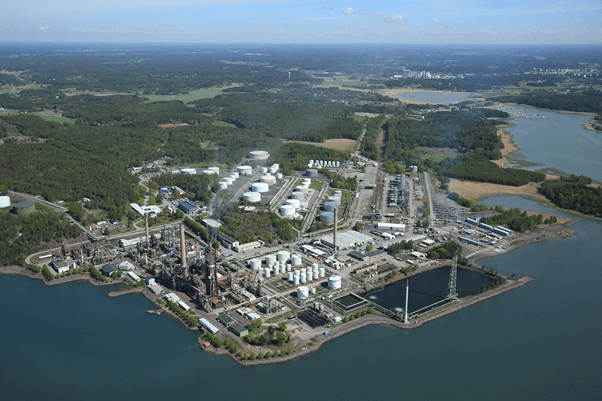

Neste’s Naantali refining facility will officially close its doors in March 2021. Source: Neste

Transition in refining

“Neste itself decided to close its facility in Naantali, Finland,” Ms Ukkonen says. In a statement released last year relating to the closure, Neste said that it did not expect fossil fuel demand to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Neste wasn’t the only refiner that took action. Total announced that it would be converting its Grandpuits refinery (Seine-et-Marne, France) to a zero-crude platform, set to be fully functioning by 2024. Shell announced that it will have its crude processing capacity at its 500,000 bpd Pulau Bukom refinery in Singapore, with the facility pivoting from a crude oil, fuels-based product slate towards new, low-carbon value chains. BP also stated its aims to cut refining throughputs on eight operated refineries from 1.7mn bpd to 1.5mn bpd in 2025 and 1.2mn bpd in 2030. This lull in demand evidently enabled the sector to explore and expedite its energy transition plans. For Neste’s Sveta Ukkonen, this response is natural: “This is how the refining industry is going to adapt to the change”. Plant conversions such as those seen by Shell and Total prove that existing refinery infrastructures can be adapted to produce alternative fuels, meaning that the marine fuel sector will ideally not be waiting on new facilities to be built.

An industry capable of change

“Neste itself decided to close its facility in Naantali, Finland,” Ms Ukkonen says. In a statement released last year relating to the closure, Neste said that it did not expect fossil fuel demand to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Neste wasn’t the only refiner that took action. Total announced that it would be converting its Grandpuits refinery (Seine-et-Marne, France) to a zero-crude platform, set to be fully functioning by 2024.

Shell announced that it will have its crude processing capacity at its 500,000 bpd Pulau Bukom refinery in Singapore, with the facility pivoting from a crude oil, fuels-based product slate towards new, low-carbon value chains.

BP also stated its aims to cut refining throughputs on eight operated refineries from 1.7mn bpd to 1.5mn bpd in 2025 and 1.2mn bpd in 2030. This lull in demand evidently enabled the sector to explore and expedite its energy transition plans.

For Neste’s Sveta Ukkonen, this response is natural: “This is how the refining industry is going to adapt to the change”. Plant conversions such as those seen by Shell and Total prove that existing refinery infrastructures can be adapted to produce alternative fuels, meaning that the marine fuel sector will ideally not be waiting on new facilities to be built.

No immediate threat

Although the global marine fuel sector may be undergoing drastic change, the overall immediate threat to HSFO is fairly minimal. The initial decline in HSFO-demand came more as a reaction to pandemic-related cost fluctuations throughout the fuel sector, than as a direct result of IMO 2020. In its 2021 outlook report, Lloyd’s List published a series of polls taken from its 2021 Shipping Outlook Forum panel combined with the company’s wider community. One poll anticipates that efficiency retrofits of ships will be a more popular form of investment for the coming year than zero-carbon research and development (see Poll 1). For as long as retrofitting existing vessels with scrubbers remains viable, we can be sure to see HSFO as a weighty presence in short-term fuel markets.

Innovative (fuel/energy) solutions for mid- to long-term:

Besides SOx, CO2 is also a major issue. Long-term alternatives must be developed if the marine industry is going to reach emissions targets by 2030 and 2050. Some of the most favoured alternatives (see Poll 2):

Hydrogen / Green ammonia – Although nearly all hydrogen is produced with fossil fuels, it can be produced through electrolysis using wind or solar. This process is expensive, and currently just 0.1 per cent of hydrogen is made using it, but this is where the main hope lies for a climate-friendly shipping fuel.

Biofuels – Sustainable marine biofuels offer ship operators a way to reduce a vessel’s CO2 emissions by 80-90%. They eliminate SOx emissions, cut NOx emissions by up to 10% and reduce particulate matter expelled in a ship’s exhaust plume by 50%. But progress is slow due to the inefficient process methods for producing biofuels.

Nuclear – Following the example of the US nuclear navy, the IMO identifies small modular nuclear reactors to be another viable alternative for powering ships. Whilst still producing GHGs, the amount is 60% lower than traditional ships, and nuclear-powered ships can move 50% faster than oil-fired ships of the same size. Although more work will need to be done before nuclear can be considered an option beyond 2050, we may see significant rise in its use in the years leading up to that.

Battery-powered – An unexpected breakthrough has come in the development of battery-powered vessels. Japanese consortium, e5 Lab Incorporated, announced its work on an electric tanker due to be in service in bunkering operations in Tokyo Bay by 2022. This could be an important development for the marine sector in terms of its fuel-alternative future.

About this Featured Story

This Featured Story is an abstract of the 4 page Featured Story in our Stainless Steel Magazine. To read the full Featured Story and many more articles, subscribe to our print magazine.

“Every two weeks we share a new Featured Story with our Stainless Steel community. Here you can find here the online abstract, and you can access the full story in our print magazine. Join us and let’s share your Featured Story on Stainless Steel World online and in print.”

– FEATURED STORY BY ELLIE PRITCHARD

All images were taken before the COVID-19 pandemic, or in compliance with social distancing.